| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Archives in the peat

A treasury of archaeology

When bogs first started to grow and expand over the landscape, people were already

living around them. Much of what we know about the environment in which the

earliest Irish communities lived comes from the pollen chronicle, which the

bogs have kept over the millennia, recording the history of vegetation change

since the Ice Age. But the bogs have also preserved many other riches, which

throw light upon Irish history and prehistoric times. An account of such valuable

archaeological objects found in bogs would fill a big book of several volumes.

There are thousands of them, ranging from tools, weapons and ornaments of metal,

stone and wood to articles of clothing, blocks of butter and human bodies. Many

stores of late Bronze Age objects have been found in bogs, strongly suggesting

that they were deliberately left there as ritual deposits.

When bogs first started to grow and expand over the landscape, people were already

living around them. Much of what we know about the environment in which the

earliest Irish communities lived comes from the pollen chronicle, which the

bogs have kept over the millennia, recording the history of vegetation change

since the Ice Age. But the bogs have also preserved many other riches, which

throw light upon Irish history and prehistoric times. An account of such valuable

archaeological objects found in bogs would fill a big book of several volumes.

There are thousands of them, ranging from tools, weapons and ornaments of metal,

stone and wood to articles of clothing, blocks of butter and human bodies. Many

stores of late Bronze Age objects have been found in bogs, strongly suggesting

that they were deliberately left there as ritual deposits.

The implications of the Lough Boora discoveries for understanding the relationship between people and bogs in Ireland are profound. The charcoal from the hearths of Lough Boora were dated using radiocarbon as being 8,400 to 9,000 years old, suggesting the presence of human communities here in the heart of Ireland in the Early Mesolithic. Artefacts were also found in the vicinity of the hearths, e.g. more than 200 tell-tale microliths from the Mesolithic. Buried together with these were the remains of the meals eaten by the toolmakers: burnt bones of red deer, wild boar, hares, birds and small fish; the only plant remains were hazel shells. There was a lot of pine in the pollen profile, and oak and elm were consistently present. The small amount of ericaceous pollen shows that bogs had not yet expanded very far. This discovery moved the accepted date for the colonisation of the Irish Midlands back over three millennia earlier. It is thus almost beyond doubt that human communities were present little more than 500 years after the end of the Ice Age throughout the landscape of lakes which preceded the bogs. We can be sure that when the large raised bogs are stripped away to reveal more ancient shorelines, more evidence of early human settlement will come to light. People came to Ireland before the bogs and their cultural evolution has thus taken place alongside the evolution of the boggy landscape, which has always played an important role in Irish cultural development.

The Dowris Hoard

The Iron Age is said to have begun about 500 B.C. The division of Irish prehistory into three distinct periods is often criticised by scholars who wish to add sophisticated refinements and make the categories more realistic. Thus the Irish Bronze Age is divided into several periods based on the type of bronze finds. The Dowris Bronze is referred to as the type of bronze associated with the later Bronze Age.

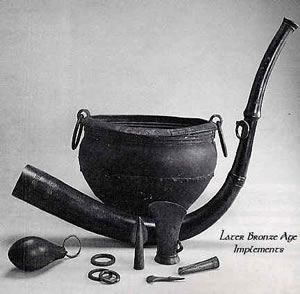

But perhaps we ought to go back to the beginning at this point - to Dowris in the

1820s. One day in early summer around 1825, two men were trenching potatoes

in the Derreens on the shore of Lough Coura at Dowris near Whigsborough, a few

miles north-east of Birr in County Offaly. This is only 8km south-west of Lough

Boora, at the very southern end of the same bog complex. All thought of potatoes

must have vanished from their minds at the sight of the fantastic hoard of gold-coloured

bronze objects which they unearthed with their spades: several hundred of them,

javelins, axe and spear-heads, mysterious pendulous ovoid bronzes, horns of

bronze, a cauldron of bronze - enough to fill a horse's cart. At the time of

the find, Lough Coura covered about 100 acres of open water, and was 172 feet

deep. The objects were removed and collected by the Earl of Rosse and T. D.

Cooke. Cooke reported the find to the Royal Irish Academy in 1848.

But perhaps we ought to go back to the beginning at this point - to Dowris in the

1820s. One day in early summer around 1825, two men were trenching potatoes

in the Derreens on the shore of Lough Coura at Dowris near Whigsborough, a few

miles north-east of Birr in County Offaly. This is only 8km south-west of Lough

Boora, at the very southern end of the same bog complex. All thought of potatoes

must have vanished from their minds at the sight of the fantastic hoard of gold-coloured

bronze objects which they unearthed with their spades: several hundred of them,

javelins, axe and spear-heads, mysterious pendulous ovoid bronzes, horns of

bronze, a cauldron of bronze - enough to fill a horse's cart. At the time of

the find, Lough Coura covered about 100 acres of open water, and was 172 feet

deep. The objects were removed and collected by the Earl of Rosse and T. D.

Cooke. Cooke reported the find to the Royal Irish Academy in 1848.

Fortunately a considerable amount of material found at Dowris is still existent in the collections of the British Museum and the National Museum of Ireland. Archaeologists have dated the Dowris material to about 7th century B.C. thus marking the first phase in the Irish late Bronze Age. Presumably this dating is based on the superior quality of the metalwork, and the finding of considerable numbers of decorative bronze pieces such as bracelets and dress fasteners.

More recently archaeologists have tried to explain the significance of such a large find at one site. John Coles suggests that Dowris must have been a central offering place because the find of almost 200 pieces was so large.

Of these 200 items 190 are accounted for: 111 in the National Museum of Ireland and 79 in the British Museum. Forty-four spearheads were found, forty-three axes, twenty-four trumpets, and forty-four crotals - a kind of bell or chime instrument, unique to Ireland. A bronze bucket - constructed of sheets of bronze riveted together - was also found and is considered to be an imported item. Two other buckets, presumed to be native copies, were also found.

The find also included five swords, most of them similar in design to weapons used

in the south of England of that time. The spearheads held a leaf-shaped design

from an earlier age, with one exception, where a lunate opening decorated the

spearhead blade. The axe-heads had sockets for easier attachment and are typical

of this time period. Other tools found include gouges, chisels and knives, which

would have been used by woodworkers.

The find also included five swords, most of them similar in design to weapons used

in the south of England of that time. The spearheads held a leaf-shaped design

from an earlier age, with one exception, where a lunate opening decorated the

spearhead blade. The axe-heads had sockets for easier attachment and are typical

of this time period. Other tools found include gouges, chisels and knives, which

would have been used by woodworkers.

The 'crotals' have caused some controversy concerning their use: it is not known whether they were used as tradesmen's weights, musical instruments or - as was suggested by John Coles - representations of a bull's scrotum, and thus part of a fertility cult associated with bulls.

The musical horns are similar in appearance to bull's horns and would have made a deep bellowing sound when played. A great number of these bronze horns survived at Dowris, twenty-four in total. They are either straight or curved and some have small conical spikes placed near the non-playing end. The horns were blown either from the side or the end depending on the design. Recent experiments have shown that the horns are capable of producing a wide variety of sounds. The method of playing is similar to that employed for playing the didgeridoo, an instrument of the Australian aboriginal people.

Music from the past

The horns were cast in two-piece moulds. The Dowris hoard, however, also contained vessels made of individual bronze sheets riveted together, such as the bucket, which was imported from Eastern Central Europe around the 8th century B.C. There was also a cauldron containing many of the smaller items found at the Dowris site. This leads to the assumption that this was not really a "hoard" of objects but a "votive deposit". If this were so, it would technically mean, that whoever finds such items can sell them on as they are not covered by 'treasure trove' laws.

Many of the publications dealing with the Bronze Age describe the cast bronze horns as instruments of war, thus confusing them with the sheet bronze trumpets and carnix of the Iron Age. To confirm this "war trumpet theory" authors point out the large amounts of swords etc, which have survived from that time.

However, following the rediscovery of the musical properties of the horns and the subsequent exploration and research it is now thought highly unlikely that these instruments were ever used in battle. Several reasons support this conclusion. Firstly, it is quite clear that each horn required an enormous amount of skill, labour and wealth to manufacture. If war trumpets were needed, long cow horns would make a louder and far cheaper alternative; such war horns were used in Scotland until quite recently. Secondly, a player will not achieve the mysterious sound from any of the Bronze Age horns by blowing too hard for the sake of volume. The best results are achieved by finding the natural internal pressure of the instrument and playing "around" it; only then does the horn begin to produce the beautiful, rich harmonics and overtones, which make it unique. Played in this way, the sounds produced are in no way loud or angry, but rather mellow, haunting and deeply evocative. By no means could it be considered rousing, frightening or intimidating.

Most likely, Irish Bronze Age horns were either used as very fine musical instruments, which they undoubtedly are or as sacred ceremonial horns, which were played with bells for religious and other gatherings. There is every reason to believe that Irish musicians during the Bronze Age travelled and came together to swap tunes and play sessions and fleadhs (festivals), in much the same way they do today. Therefore, we may have found sites of great festive gatherings, where musicians played together, wherever we find collections of many horns. The recent discovery that most of the surviving original horns have a common tuning and relative pitch to each other would support this idea. This phenomenon can be clearly heard on the Coirn na hEireann recording of original instruments from the National Museum of Ireland.

Have a look at this website: Prehistoric music in Ireland

The hoard from Dowris would be astonishing enough if it were unique, but more than 50 other Bronze Age hoards have been found in similar or related contexts, laid to rest in bog lakes all over the country during the Late Bronze Age. The earlier hoards tend to occur in peat which is highly humified, and was accumulating slowly at the time the hoards were deposited; the later ones by contrast occur in peat which is only slightly humified. The majority are Late Bronze Age; there are only five Middle Bronze Age hoards.

Buried - drowned - burnt

Prehistoric man was much more exposed to and dependent on inexplicable and superior forces than we are today. This is expressed in offering rituals where objects or beasts were sacrificed to please the mighty forces. In central European archaeological finds, only sparse material remains of these spiritual offerings, which - during the Bronze Age - were preferably undertaken in open landscapes are found.

Thoughts of ritual offerings, help us to interpret important and much-dicussed collection sites of Bronze Age objects: `deposits' is a term for all deliberately laid down objects, which are not connected to burial sites or settlements. Our view of such deposits is based on collective findings of numerous metal objects of varying degree of wear ranging from newly cast, to broken or strongly weathered. Stoneware, pottery, plants, animals, human beings or parts thereof were also deposited or sacrificed. Why these objects were laid down is much more difficult to answer for each individual deposit. The multitude of reasons behind such rituals can only be roughly outlined. It is most likely that Bronze Age deposits may be considered as evidence or remains of ritual habits. They may have been laid down as offerings, as items for the hereafter or for keeping them from becoming profane after ritual use.

To answer questions arising on the how and why of ritual deposits, scientists have begun systematic analyses of their localities and contents in the last decades. These studies have discovered that although individual deposits differ greatly, some common patterns concerning their locations and contents of the various items have been discovered. Several types of objects have only or primarily been found in deposits, like some types of early Bronze Age daggers, ceremonial metal shields or helmets. When interpreting deposits as sacrificial offerings, one must consider the immense values of the objects that were offered. Especially through deposits containing many metal objects it is often possible to estimate the wealth of a region.

Findings from peat bogs are classed into their own category based on their content, since we can only seldom distinguish, whether the objects were deposited into a lake, a swamp or a peat bog.

It is not without reason that still waters and sinister bogs play such an important role in ethnic beliefs; their strange atmosphere was surely both fascinating and frightening for people in the Bronze Age and gave these places mystical meaning.

Such remote bodies of water were regarded as sacred and looked upon with veneration in these early times. The collections found here probably represent deposits not from single acts of hoarding but accumulations over many years, and perhaps centuries, of annual or seasonal offerings. It is also possible that the 19th-century veneration of Holy Wells on the opposite edge of the bog, at Crancreagh 4 km to the north-west, and at Lug 4.25km to the north, developed as a "copy" or revival of the Bronze Age tradition so spectacularly demonstrated by the Dowris Hoard. Let's return to Lough Coura itself: by the end of the century the lake had turned into a reedmarsh and in 1934 R. L. Praeger described it as an extensive limy marsh. Even the marsh has almost vanished today, and much of this once fascinating area of fen and lake has been smothered under coniferous woodland.

Many of the objects discovered in the bog were probably things lost in the normal daily course of events, but other finds like the hoard of Dowris are more unusual. Where hoards of objects are found together they are believed to be the stock of itinerant traders, and it is difficult to imagine these being casually lost or misplaced. But these "traders' hoards" have turned up fairly often, and they nearly always occur in bogs.

Images:

Early prehistoric Landscape of the Dowris area

Detailed drawings:

Literature:

John Coles, Dowris and the Late Bronze Age of Ireland, a footnote, JRSAI no.101, pp164-5. 1971;

G. Eogan, Hoards of the Irish Later Bronze Age, Dublin 1983;

John Feehan u. Grace O´Donovan, The Bogas of Ireland. An Introduction to the Natural, Cultural and Industrial Heritage of Irish Peatlands, Dublin 1996, 449-473;

Wolf Kaubach, Vergraben, versenkt, verbrannt - Opferfunde und Kultplätze, In: Albrecht Jockenhövel u. Wolf Kubach (Hgg.), Bronzezeit in Deutschland, Stuttgart 1994, 65-74.

|

|

|

|